In both of its celebrated incarnations, Duel (1971) marked major turning points in Matheson’s career. He considered his short story, published in Playboy in April of 1971, to be the ultimate embodiment of his leitmotif—which he defined in his Collected Stories as “the individual isolated in a threatening world, attempting to survive”—and thus his farewell to the literary form in which he had made his professional debut some two decades earlier with “Born of Man and Woman.” Fortunately, said farewell was less than definitive, as recently shown by the appearance of “The Window of Time” (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, September-October, 2010).

Broadcast as an ABC Movie of the Week that November, the film was Matheson’s maiden effort in the burgeoning format of the TV-movie, with which he enjoyed some of his greatest successes of the 1970s, and marked the first full-length directorial effort by the twenty-four-year-old Steven Spielberg. It would be but one of several projects on which they collaborated, including Twilight Zone—The Movie (1983) and Amazing Stories, for which Matheson served as a creative consultant during the anthology show’s second and final season. Spielberg is also an executive producer on the upcoming Real Steel, based on Matheson’s “Steel,” previously a classic Twilight Zone episode.

The event that led to this seminal tale was an even bigger turning point for the nation, as it was inspired by a real-life incident that happened to Matheson and his friend and colleague Jerry Sohl on November 22, 1963, the day President John F. Kennedy was killed. The two men had been playing golf when they learned of the assassination and, naturally too distraught to continue, they headed home, only to be tailgated at high speed through narrow Grimes Canyon by an apparently crazy truck driver. His writer’s mind always active, in spite of the double trauma they had been through, Matheson grabbed a piece of Sohl’s mail and jotted down the idea that became “Duel.”

In the intervening years, Matheson—by then a prolific writer of episodic television—pitched the idea to various series, but ironically was told that it was “too limited,” so he eventually decided to write it as a story. This was spotted in Playboy (one of Matheson’s most frequent outlets for short fiction) by Spielberg’s secretary, and the director, a longtime Twilight Zone fan, thought it might be the perfect vehicle, as it were, for his feature-length debut. Spielberg earned his spurs with “Eyes,” a segment of Rod Serling’s 1969 Night Gallery pilot, and directed episodes of that series as well as Marcus Welby, M.D., The Name of the Game, The Psychiatrist, and Columbo.

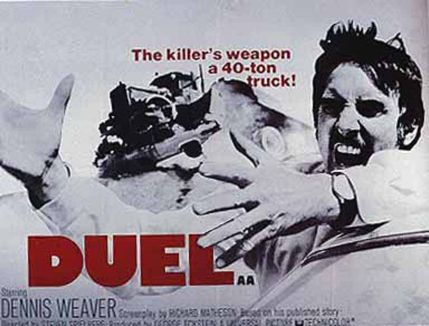

The premise of Duel is deceptively simple: a traveling salesman (Dennis Weaver) impatiently passes a smoke-belching gasoline tanker truck on a lonely California highway, literally setting in motion a deadly game of cat and mouse with the driver, whose face he never sees. Matheson’s taut teleplay, Spielberg’s flair for visuals and action, and Weaver’s casting as the aptly named “Mann” made it an exercise in nail-biting suspense. Then starring in McCloud, and best known for his Emmy-winning role on Gunsmoke, Weaver was cast primarily because Spielberg admired his performance as the high-strung motel night manager in Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil (1958).

Both Matheson and Spielberg used ingenious methods to create their respective versions of Duel. Matheson (who praised Spielberg for adding “his own incredible touch” to the script) wrote the first draft of the story in one sitting after driving from his home to Ventura and back, dictating what he saw along the way into a tape recorder, in order to provide Mann with a realistic route. Instead of using storyboards, Spielberg visualized the entire film by plotting it out on a mural that depicted the highways north of Los Angeles in Pearblossom, Soledad Canyon, and Sand Canyon near Palmdale, California, which covered the walls of his motel room during the thirteen days of location shooting.

Hailed by Cecil Smith of The Los Angeles Times as the “best TV-movie of 1971…a classic of pure cinema,” Duel won an Emmy for best sound editing and a nomination for Jack A. Marta’s cinematography; it also garnered a Golden Globe nomination as the Best Movie Made for TV. Realizing what a hit it had on its hands, Universal had Spielberg write and direct three additional scenes to bring the 74-minute movie up to 90 minutes, so that it could be released theatrically in Europe in 1973 and domestically in 1983. The film underwent one last transformation when it was cannibalized for an episode of The Incredible Hulk, “Never Give a Trucker an Even Break.”

That indignity aside, Duel has had an amazing afterlife, serving as the apparent inspiration for films ranging from George Miller’s Mad Max trilogy to John Dahl’s Joy Ride (2001) and such stories as Stephen King’s “Trucks.” King and his son, Joe Hill, contributed “Throttle,” a story inspired by “Duel,” to Christopher Conlon’s He Is Legend tribute anthology. The oft-reprinted original headlined Tor’s collection Duel: Terror Stories by Richard Matheson and was published with the script—plus an afterword by Matheson, an interview with Weaver, and a selection of concept art for the theatrical release—in Duel & The Distributor (which I edited for Gauntlet).

Matthew R. Bradley is the author of Richard Matheson on Screen, now on sale from McFarland, and the co-editor—with Stanley Wiater and Paul Stuve—of The Richard Matheson Companion (Gauntlet, 2008), revised and updated as The Twilight and Other Zones: The Dark Worlds of Richard Matheson (Citadel, 2009). Check out his blog, Bradley on Film.